“At the peak of the pandemic, the virus began mutating toward a less lethal form. This makes sense if the virus was immature when it erupted, evolved into a more lethal form after many passages through the human body before it became less lethal. It is entirely possible that the virus became less lethal because its numbers had increased to a point that the chances of it passing through a human body that wasn’t already infected reduced”

Raggie Jessy Rithaudeen

ڤندميق سلسما يڠ بونوه لبيه 50 جوت اورڠ ڤد تاهون 1918

Sertai saluran Telegram TTF di sini

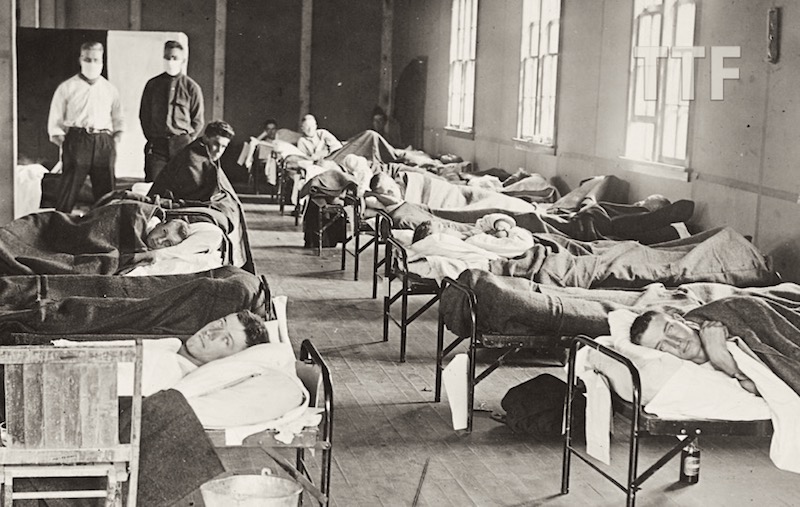

Credit: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Center for Bioenvironmental Research at Tulane and Xavier Universities

“In handling any crisis, it is absolutely crucial to retain credibility. Giving false reassurance is the worst thing one can do. Holding on to crucial information may just be as bad, as the minute people begin to believe that officials know more than they say, public trust in the government would crumble like a mansion built on sand”

Raggie Jessy Rithaudeen

The world today is quickly coming to terms with the spread of Covid-19 respiratory infections, now at pandemic proportions, caused by the novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 strain. At the time of writing (7.12 am, 12th September, 2021), the disease caused 4.55 million deaths worldwide, with the United States reportedly being the hardest hit (660,000-plus deaths). We’re way into the third wave in Malaysia, and new variants are quickly dashing hopes of ever reaching herd immunity.

The head of the WHO in Europe is already setting the stage for what might become routine vaccination, expressing doubts that existing vaccines have the capacity to end the Covid-19 pandemic. Faced with the possibility that the virus may be around for many years, Dr Hans Kluge posits that health officials must now “anticipate how to gradually adapt our vaccination strategy,” in particular, the question of additional doses. But that’s the here and now, and very possibly, the not-too-distant future.

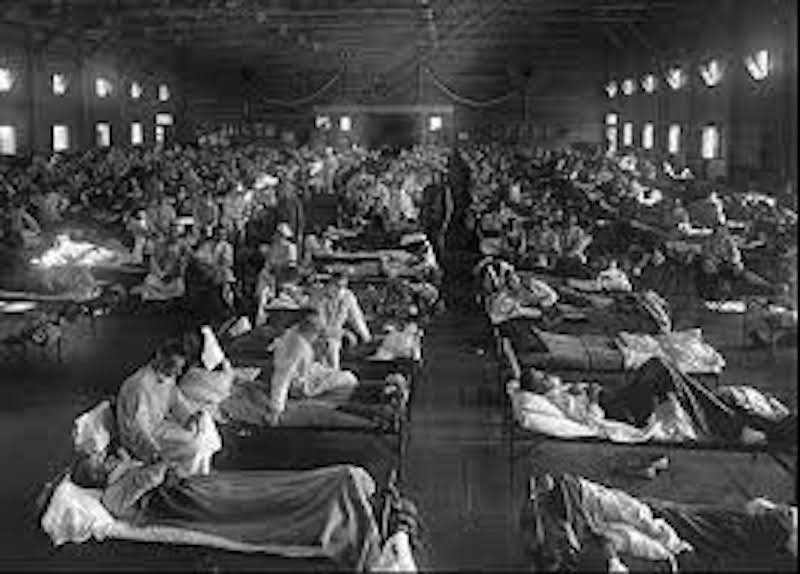

In 1918, the world was struck with a similar pandemic caused by the HiN1 virus that led to lethal forms of a respiratory ailment, known today as the Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS). The pandemic is said to have killed more people in absolute numbers than any other disease outbreak in history, with scientists constantly revising the death toll. While contemporary estimates put the toll at 21 million, a 2002 study seems to indicate that the deaths were between 50 and 100 million people.

Given that the world population in 1918 was only 28 percent of what it is today, adjusting for population, a comparable toll would be 175 to 350 million deaths today. A letter from a physician at one United States Army camp to a colleague put a more human face on those numbers:

“These men start with what appears to be an ordinary attack of LaGrippe or Influenza, and when brought to the Hosp. they very rapidly develop the most vicious type of Pneumonia that has ever been seen … and a few hours later you can begin to see the Cyanosis extending from their ears and spreading all over the face, until it is hard to distinguish the colored men from the white. It is only a matter of a few hours then until death comes…. It is horrible. One can stand it to see one, two or twenty men die, but to see these poor devils dropping like flies…. We have been averaging about 100 deaths per day…. Pneumonia means in about all cases death…. We have lost an outrageous number of Nurses and Drs. It takes special trains to carry away the dead. For several days there were no coffins and the bodies piled up something fierce…. It beats any sight they ever had in France after a battle. An extra long barracks has been vacated for the use of the Morgue, and it would make any man sit up and take notice to walk down the long lines of dead soldiers all dressed and laid out in double rows…. Good By old Pal, God be with you till we meet again.”

The Virus Itself

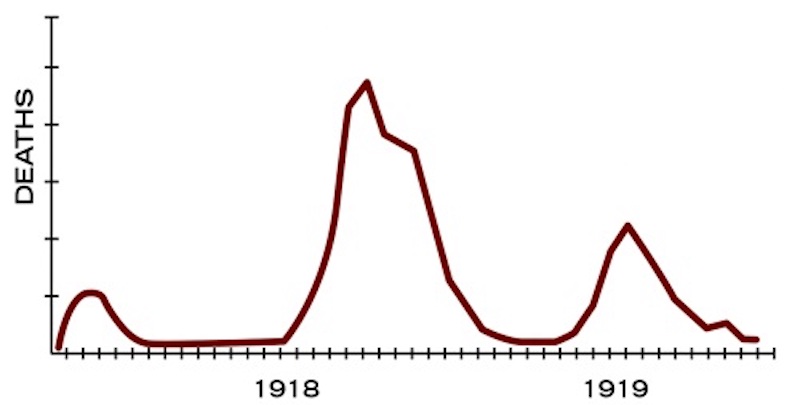

The ‘Spanish flu’, as it came to be known, began quite mildly with a spring wave that started in March 1918, subsiding by the summer of 1919. In fact, it was so mild that some physicians began to wonder if the disease was actually influenza. Several Italian doctors argued that the “febrile disease now widely prevalent in Italy is not influenza.” British doctors seemed to concur, with one group of researchers arguing that the spring epidemic was not influenza because the symptoms, though similar to influenza, were “of very short duration and so far absent of relapses or complications.”

But hell was about to break loose.

Within weeks, a second pandemic wave swept across the world (in the fall of 1918) and accounted for most infections and deaths. A third wave followed during the winter and spring of 1919, adding to the pandemic death toll before subsiding during the summer of 1919.

In the second wave, not only was the virus extremely lethal, it was extraordinarily violent and created a range of symptoms rarely seen. Symptoms were so unusual that the influenza was initially misdiagnosed as dengue, cholera, or typhoid. One observer wrote, “One of the most striking of the complications was hemorrhage from mucous membranes, especially from the nose, stomach, and intestine. Bleeding from the ears and petechial hemorrhages in the skin also occurred.”

In isolated human populations, the virus killed at even higher rates. In the Fiji islands, it killed 14 percent of the entire population in 16 days. In Labrador and Alaska, it killed at least one-third of the entire native population. But perhaps the most disturbing fact was this – the lungs of those infected resembled those of poison gas victims. So violent was the outbreak, many who succumbed to injuries died not because of secondary pneumonia complications, but due to the virus itself.

Treatment and Prevention in 1918

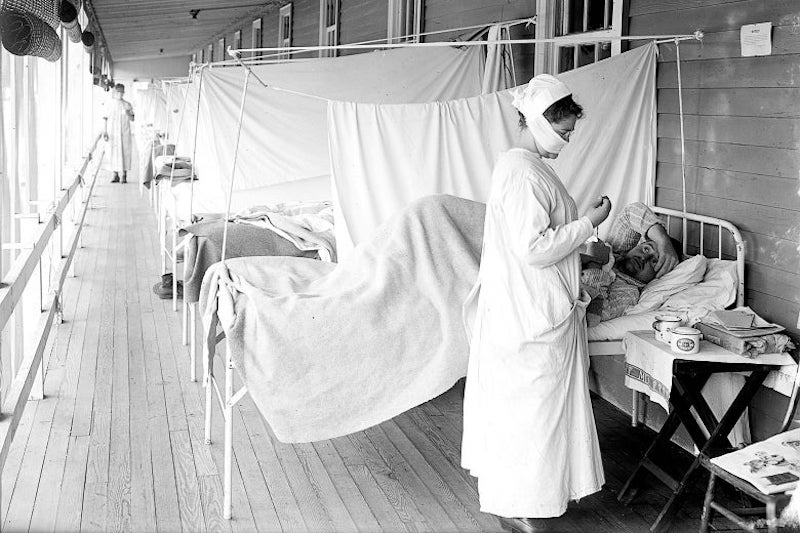

Physicians tried everything they knew and heard of, ranging from the ancient art of bleeding patients to the administration oxygen, even developing new vaccines and sera. Only one therapeutic measure, the transfusion of blood from recovered patients to new victims, showed any hint of success.

But many nonmedical interventions did succeed. Total isolation and cutting a community off from the outside world did work when it was done early enough. Gunnison, Colorado, a town that was a rail center and was large enough to have a college, succeeded in isolating itself. American Samoa escaped without a single case, while a few miles away in Western Samoa, 22 percent of the entire population died.

Even if isolation only slowed the virus, it had some value. One of the more interesting findings in 1918 was that the later in the second wave someone got sick, not only was he (or she) less likely to die, his (or her) illness was more likely to be mild. This was true in terms of how late in the second wave the virus struck a given area. That is to say, cities struck at later dates tended to suffer less, while individuals in a given city who were struck later also tended to suffer less.

One obvious hypothesis that might explain this phenomenon is the improvement in medical care as health care workers learned how to cope with the disease. But this hypothesis collapses upon examination – in a given city, as the epidemic proceeded, medical care disintegrated. Doctors and nurses were overworked and sick themselves, and victims—possibly even a majority of victims—received no care at all late in an epidemic.

A second hypothesis that the most vulnerable people were struck first also fails. For the hypothesis to be true, Americans on the east coast had to have been more vulnerable than those on the west coast, and Americans and western Europeans had to have been more vulnerable than Australians. But this wasn’t the case at all.

Another hypothesis, though entirely speculative, may be worth exploring. If one steps back and looks at the entire United States, it seems that people across the country infected with the virus in September and early to mid-October suffered the most severe attacks. Those infected later, no matter which part of the country they were, suffered less.

This indicates that the virus began mutating toward a less lethal form at the peak of the pandemic. This makes sense if the virus was immature when it erupted, evolved into a more lethal form after many passages through the human body before it became less lethal. It is entirely possible that the virus became less lethal because its numbers had increased to a point that the chances of it passing through a human body that wasn’t already infected reduced.

Social Disruption and Public Health Lessons

Back when the Spanish flu stuck, many countries were involved either directly or indirectly in World War I. Those involved tried hard to control public perception so as to avoid hurting morale. As a result, the press in countries fighting in the war did not mention the outbreak even during the nonlethal first wave. But Spain was not at war and its press wrote about it, hence the term “Spanish flu.”

The combination of rigid control and disregard for truth had dangerous consequences. Focusing on the shortest term, local officials almost always told half-truths or outright lies to avoid damaging morale and the war effort. They were assisted—not challenged—by the press, which, although not censored in a technical sense of the word, cooperated fully with the government’s propaganda machine.

As the disease approached a city or town, local officials would tell the public not to worry, that public health officials would prevent the disease from striking them. When the disease finally struck, officials would routinely insist that it was only ordinary influenza, not the Spanish flu. As the epidemic exploded, officials assured the public almost on a daily basis that the worst was over.

In Philadelphia, when the public health commissioner closed all schools, houses of worship, theaters, and other public gathering places, one newspaper went so far as to say that the order was “not a public health measure” and reiterated that “there is no cause for panic or alarm.” But as people heard these reassurances, they could see neighbours, friends, and spouses dying horrible deaths.

In Chicago, the mortality rate of all influenza admissions at the Cook County Hospital was 39.8 percent. In Philadelphia, bodies remained uncollected in homes for days until eventually, open trucks and even horse-drawn carts were sent down city streets and people were told to bring out the dead. The bodies were stacked without coffins and buried in cemeteries in mass graves dug by steam shovels.

This horrific disconnect between reassurances and reality destroyed the credibility of those in authority. People felt they had no one to turn to, no one to rely on, no one to trust.

Ultimately, society depends on trust. Without it, society began to come apart. Normally in 1918 America, when someone was ill, neighbours helped. That did not happen during the pandemic.

As pressure from the virus continued, an internal Red Cross report concluded, “A fear and panic of the influenza, akin to the terror of the Middle Ages regarding the Black Plague, has been prevalent in many parts of the country.” A prominent scientist, Victor Vaughan, wrote, “If the epidemic continues its mathematical rate of acceleration, civilization could easily … disappear … from the face of the earth within a matter of a few more weeks.”

One lesson is clear from this experience – in handling any crisis, it is absolutely crucial to retain credibility. Giving false reassurance is the worst thing one can do. Holding on to crucial information may just be as bad, as the minute people begin to believe that officials know more than they say, public trust in the government would crumble like a mansion built on sand.

WAJIB BACA:

Muhyiddin, Khaled Nordin berakal labah-labah, di gua buruk suka merakut