Zaidi Azmi

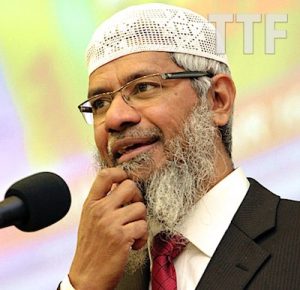

Conflicting statements have rendered the actual status of the request by India for Malaysia to extradite Mumbai-born Muslim preacher Dr. Zakir Naik rather confusing. There is also the not totally unexpected moves by ministers to be involved, although it’s outside their jurisdiction.

While Prime Minister Tun Dr. Mahathir Mohamad had last week reiterated his flat-out rejection of the request, one of his ministers indicated otherwise.

Communications and Multimedia Minister Gobind Singh Deo on Thursday said that India would need to submit its case against Zakir before the government could decide on deportation.

Another minister, M. Kulasegaran (Human Resources) also wants to be involved and said yesterday that he would raise the issue once he had the opportunity to meet with India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi.

He issued a statement on Friday to say this: “I assure the people that when I go to India and if I have the chance to meet Modi, I will discuss this with him.”

Kulagesegaran was echoing Gobind’s statement about following the rule of law on the matter.

To the unfamiliar, Zakir, who left India in 2016, is currently being hunted by India following allegations that his lectures had inspired a number of terrorists in Bangladesh.

Gobind’s take on the matter however did not tally with Mahatir’s stand in not wanting to hand over Zakir to India as long as he does not violate Malaysian laws.

Adding more to the confusion was the fact that India had already submitted an extradition request and had last week and yesterday continued to state that Malaysia was perusing the request.

The extradition request was done as per the Malaysia-India mutual assistance in criminal matters that was signed in March 2012 by Malaysia’s Attorney-General Tan Sri Abdul Ghani Pattail and India’s Ministry of External Affairs secretary Sanjay Singh.

India had lost one round in court here

According to the treaty – that allows the two countries to extradite fugitive criminals and/or wanted individuals – a written request must be submitted to the respective country’s central authority, which for Malaysia is the AG.

A source from AG’s Chambers said that while India did submit such a request, there was however no news of what had become of it after a High Court here threw out an application by Hindraf to declare Zakir a threat to national security.

Attempts to get a response from the Indian High Commission here over Mahathir’s decision to allow Zakir to stay put were unsuccessful.

“I am sorry. The acting high commissioner (Nikhilesh Chandra Giri) is a very busy man. He cannot entertain you,” said Nikhilesh’s assistant.

The drama over Zakir’s stay in Malaysia has been occasionally surfacing in the last couple of years, with the most controversial being the one which stemmed from his series of comparative religion lectures in 2016.

Although Zakir has sizable detractors in Malaysia, particularly those from non-Muslim Indians, his fiercest critic was — still is — Penang Deputy Chief Minister Dr. P. Ramasamy, who in 2016 called the preacher “Satan”.

Recently Ramasamy cautioned Mahathir on how his refusal to comply with India’s request would violate the 2012 treaty.

However, international law experts who wanted to remain anonymous pointed out that the nature of charges hounding Zakir gives Malaysia a valid reason to ignore India’s request.

Citing Article 4 (1) (b) of the treaty, they say that Malaysia can refuse to assist India if the requested individual is being investigated, punished and prosecuted over his race, religion, sex, ethnic origin, nationality and political opinions.

A similar provision is in Malaysia’s Extradition Act. One part says that a fugitive and or criminal shall not be surrendered to a country seeking his return if he might be prejudiced at his trial, punished, or imprisoned because of his race, religion, nationality or political opinions.

“If India wants to argue, our government can counter by revisiting the Interpol’s decision to reject India’s request last December to put a red notice on Zakir due to political and religious bias among other reasons,” argued one lawyer.

Another option for India is to go to the International Court of Justice.

“The nature of international laws are persuasive, not compelling. And because the treaty gives Malaysia the option to refuse to cooperate, I don’t think India can successfully sue us in the international court,” said one lawyer.

READ MORE HERE